|

|

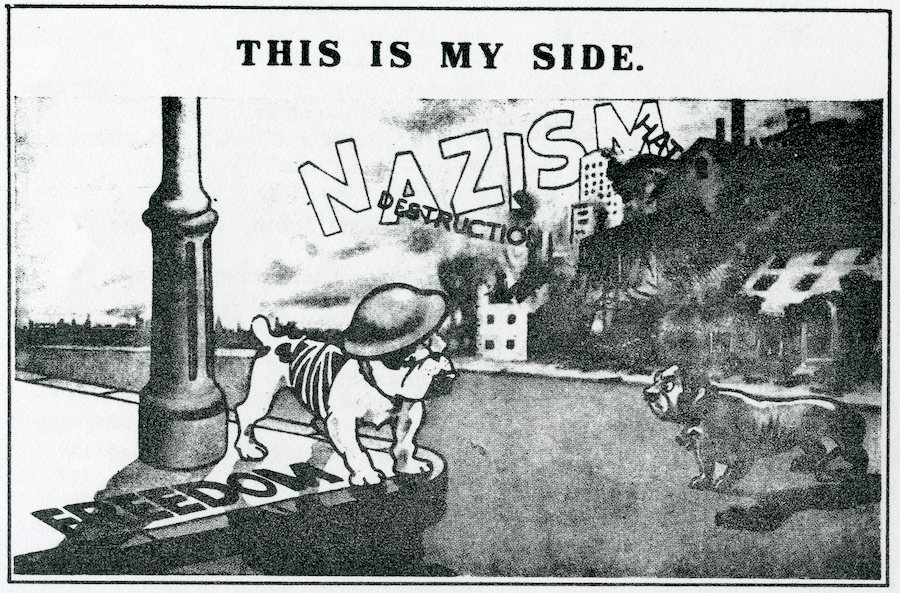

'Dad's Army' was one of

the most popular of all British TV and radio programmes. It was

often far-fetched. Yet it achieved a measure of credibility because

it was a recognisable caricature of the real thing, the Home

Guard during the Second World War. |

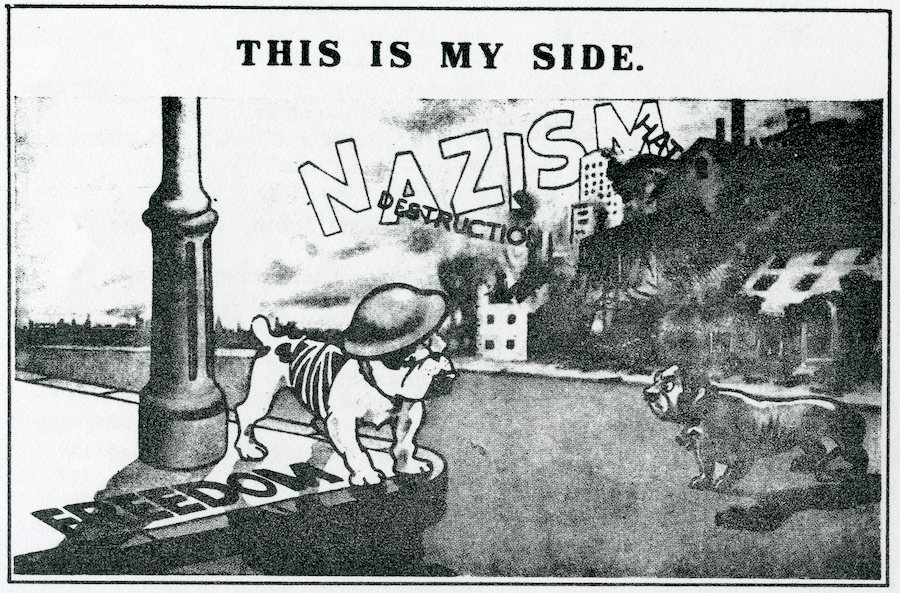

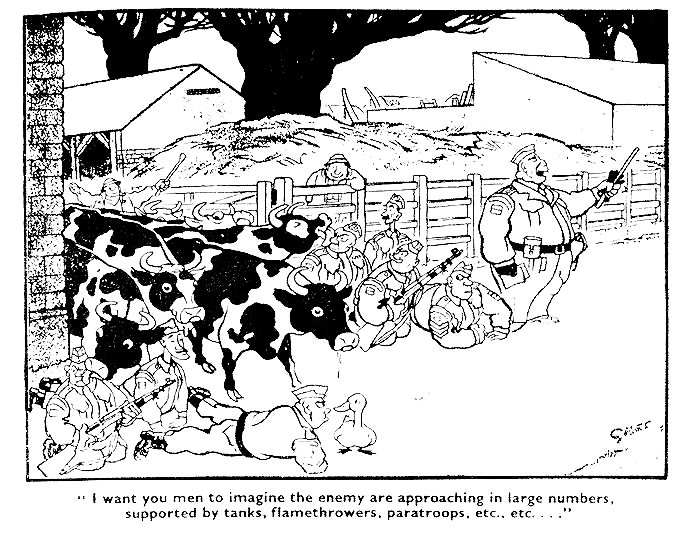

Some members of the platoon worked out a patrol based on a circuit of the pubs in our sector of Clewer and Dedworth. After all, where were spies more likely to be than in public houses where to eavesdrop on local gossip was obviously easy? These (the pubs) included the the Bricklayers Arms in Hatch Lane, the Prince Albert, the Sebastopol and the Wolf in Clewer Hill Road and the Black Horse and the Queen in Dedworth Road, with the Three Elms as the final port of call. Two of those on patrol on one occasion became a trifle too merry and let off their rifles (the ammunition fortunately was blank). This gave rise to an enquiry and discipline was accordingly tightened. Although our platoon had its training headquarters at St Katherine's Hall (now demolished) near Brickwall in Clarence Road, night patrols were based on the stables at Vale House (now also demolished). I remember one hot summer night, when the men had shed their uniforms and were immersed in a game of cards, Sir George and Col. Reid paid a surprise visit. Sir George was even less articulate than usual - to express it in more polite phraseology he was 'lost for words'. Indoor training sessions took place at St Katherine's Hall. Our sergeant, an ex-regular, would call us to order with a stentorian 'Get fell in there' and then we proceeded to go through the usual exercises such as 'naming of parts'. The correct identification of targets was another part of the training. Once I was asked to name a particular tree on the diagrammatic panorama displayed in front of us. Already a keen amateur naturalist, I volunteered the information that it was an oak tree, only to receive the crushing retort, "No, it ain't, it's a bushy-topped tree'. In such ways one learnt the logic of official nomenclature. Even the sergeant, however, knew that the most important thing of all was to finish well before closing time at the Three Elms. Occasionally we attended lectures. I remember one such at the old Playhouse Cinema by the Bridge. A tough Canadian, who had served in the International Brigade in the Spanish Civil War, demonstrated to us with the aid of a racy dialect how to make and use 'Molotov Cocktails' and other weapons of guerrilla warfare. |

The 'chair'

was taken by Sir Owen Morshead, Commander of the Castle Home

Guard and Royal Librarian, whose perfect diction matched his

tall and aristocratic appearance. I was much more fascinated

by the contrast between the Canadian rough-neck and the English

gentlemen than I was in the technicalities of placing an incendiary

device on the track of a German tank. Raymond South

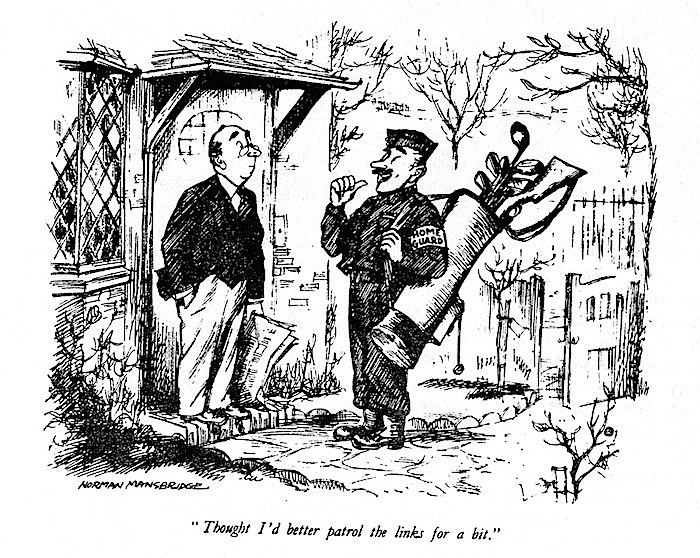

Wartime topics and photographs |