|

|

|

To the west of Windsor the land rises to

the hill which takes its name from the medieval hermitage of

St. Leonard. It is understandable that this hill, with its spring

of water on the edge of Windsor Forest, might draw a man wishing

to retreat from the world. A hermit lived a solitary life though

he was not enclosed in his cell as an anchorite would be. His

primary work was prayer but he might also undertake some other

task such as guiding travellers through waste land. Though a

religious he was not necessarily a priest, though he was one

in the case of St. Leonard's.

We do not know when the chapel was established but St. Leonard,

a 6th century frankish nobleman who became a Christian and a

hermit, was a popular dedication in the 11th and 12th centuries.

We do know that at the beginning of the 13th century William

de Braose held the right to appoint the priest, for it was in

this connection that we have the first known reference in official

records to St. Leonard's. In February 1215 the presentation of

a priest to the chapel was made by King John (Footnote 1) because

all William's possessions, including this advowson (right to

appoint) had been seized by the King. To explain the circumstances

it is necessary to look at the background.

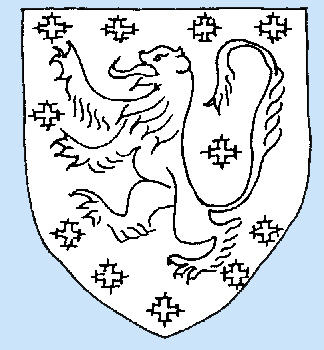

William de Braose is one of the personalities of the Middle Ages

who catches the imagination. He was the most famous member of

the de Braose family, a great lord who played an important part

in the local as well as the national scene. The possessions he

inherited and acquired by marriage in England and Wales were

immense. His great-grandfather, another William, was Lord of

Braose (or Briouze) in Normandy, whose castle lay not far from

Falaise where William the Conqueror was born. He must have been

one of the Conqueror's favoured commanders judging by the grants

of the land he received after the Conquest; according to the

Domesday Survey he had 61 manors in Berkshire besides many more

elsewhere.

William, the 4th Baron, succeeded his father in about 1187. On

John's accession to the throne in 1199 William, who was a leader

among those urging that he should be crowned, became John's close

companion in Britain and Normandy; John made him various territorial

grants and it was the non-payment of dues on these lands which

was the ostensible reason for William's later downfall. However

it seems likely that the trouble between them arose from the

King's loss of confidence in the discretion of William and especially

of his wife, Maud (sometimes called Matilda). It appears that

William was one of the few people to know what happened to John's

nephew, Arthur of Brittany, who was John's only serious rival

for the throne, being the son of John's elder brother.

This boy had been captured by John in 1202 and put in the charge

of Hubert de Burgh at Falaise. It was said that Hubert was ordered

to blind Arthur but could not bring himself to do so; Shakespeare

uses this story in 'King John'. On 24th February 1203 John gave

William the land of Gower (in South Wales) for himself and his

heirs, it was said "on account of William threatening to

depart from him and to return to England." It is possible

that William had remonstrated with the King regarding Arthur

and was bribed with Gower. William had publicly refused to take

charge of the prince.

It is believed that John killed Arthur

with his own hands, and a detailed account of the story occurs

in the Annals of Margam. The de Braose family were patrons of

this Cistercian Abbey in Glamorgan and the Annals seem to give

information supplied by William. Certainly he was at Rouen with

John at the time of S Arthur's death. The Margam account says:

"After King John had captured Arthur and kept him alive

in prison for some time, at length, in the castle of Rouen, after

dinner on the Thursday before Easter" [i.e. 3rd April 1203]

"when he was drunk and possessed by the devil, he slew him

with his own hand, and tying a heavy stone to the body cast it

into the Seine. It was discovered by a fisherman in his net .

. . (and) taken for secret burial . . ." (Footnote 2)

William, however, continued to be a close companion of the King

until his failure to pay his dues to the Crown caused a rift.

In 1207, six years after obtaining the honour of Limerick, he

had only paid 700 marks in all, instead of 500 marks a year,

and he was in arrears for his other possessions. (Footnote 3)

Then in 1208 the Interdict was laid upon England during the great

struggle between John and the Pope over the election to the Archbishopric

of Canterbury, and William's son Giles, Bishop of Hereford, was

one of the five bishops who went to France with the Primate.

John must have suspected the loyalty of the rest of the family,

and sent to William for a son as hostage against the possibility

of the Pope absolving them from allegiance to him as their sovereign.

The King's messengers were met by William but before he could

reply his wife, Maud, with a reckless lack of tact, replied that

she would entrust no son of hers to a monarch who could cause

the death of his own nephew.

In an attempt to placate the King, rich gifts were sent; it was

said that Maud sent Queen Isabella a herd of cows and a bull

all white as milk but with red ears. The King was not to be appeased.

William had already surrendered three Welsh castles in pledge

for the large sums of money he owed the Crown; now he decided

on defiance and tried to regain his castles. He failed and instead

stormed and sacked half Leominster before John could send an

army to drive the attackers away. William escaped to Ireland

and left his family with relatives there whilst he returned to

Wales where he harried the countryside. John crossed to Ireland

and besieged Maud at Meath but she managed to escape to Scotland

with her son and his wife, but they were captured in Galloway.

John returned Maud and her son to England and they were eventually

imprisoned in Windsor Castle where, it was commonly believed,

they were starved to death in 1210. Such was the vengeful ferocity

of John's wrath.

William was outlawed but escaped to France disguised as a beggar.

He died in September 1211 at Corbeil; his body was taken to Paris

and there interred by Stephen Langton, the exiled Archbishop.

Eventually the de Braose lands were recovered by the family but,

whilst they were still held by the King, John presented Geoffrey

de Meysi as priest to the chapel of St. Leonard in the Windsor

Forest, vacant by the death of Robert V Mauncell.

Later in the 13th century the advowson of St. Leonard's was held

by the Lord of Clewer and in the 14th century the most illustrious

member of the Brocas family. Sir Bernard (Footnote 4) showed an

interest in the hermitage. In 1354 he sought privileges for pilgrims

to the hermitage by writing to the Pope pleading that:

"Whereas William the hermit, chaplain of St. Leonard Loffold (Losfield), in Windsor Forest, lives a solitary life, and serves God alone, and whereas a multitude of people flock to the chapel, the Pope is prayed to grant an indulgence to those who visit the chapel a. and give alms to the fabric." (Footnote 5).

The request was acceded to, and an indulgence

d one year and forty days was granted in 1355 to those who visited

the hermitage on the feasts of Pentecost, the Assumption of the

Blessed Virgin Mary, and St. Leonard, and gave alms The grant

of an indulgence was much valued for it was believed that a remission

of that much punishment in Purgatory would be obtained as would

have been worked off by penance for the given time.

The last mention of the hermitage in official records seems to

be in conveyances of the manor in 1512, (Footnote 6) but there

is little doubt that its endowments would have been confiscated

at the Suppression of the Chantries in 1547 if it had not already

ceased to exist.

Much later there was a country house called The Hermitage on

St. Leonard's Hill. The naming of a later house after a former

building is slight evidence for the site of that building, but

here it does not seem unreasonable, as the plot of land was known

as Eremytescroft (Hermit's Field). We know that the house was

there in 1717 when William Stukeley, the antiquarian, referred

to Mr. Robert Butler as living at The Hermitage. Letters from

Frances, Countess of Hertford, in 1737 were addressed from The

Hermitage and describe the house as "old and falling into

disrepair".

The house, rebuilt in 1750, was bought in 1773 by the Duke of

Gloucester who named it Sophia Farm after his daughter born in

that year. He added it to his adjoining estate, the house of

which was known as Gloucester Lodge. In 1782 Gloucester Lodge

was bought by the 3rd Earl of Harcourt, in whose family it remained

until 1872 when it was bought by Mr. (later Sir) Frances Tress

Barry and thence became known as St. Leonard's Hill. Barry virtually

rebuilt the house, which was sold in 1924 following Lady Barry's

death, and the new owner began demolition at once. All that remains

today is a sad and dangerous ruin.

Sophia Farm became known as St. Leonard's and from 1854-1920

was owned by the Brinckman family. It was bought in 1932 by Horace

Dodge the American motor magnate who almost completely rebuilt

it. Joseph Kennedy had use of the house whilst he was American

Ambassador in London (1937-40), and it was occupied by him for

about a year. The house remained empty for a number of years

until 1966 when the estate was acquired by Billy Smart and in

1969 was transformed into the Windsor

Safari Park. [By

1996 it had become Legoland. Editor]

We have come a long way from the hermit in the quiet chapel of

St. Leonard on the Hill.

1. Victoria County History; Berkshire III p. 76.

2. WARREN W.L., 'King John' p. 99.

3. Dictionary of National Biography; Braose, William de.

4. Windlesora No. 3, p. 21.

5. Cal. Papal Pet. Vol. I p. 270.

6. V.C.H.: Berkshire III p. 76.

Also ELWES, Dudley G. Cary, 'The de Braose

family' (W. Pollard 1883).

HUNTER, Judith and others, "The changing face of Windsor:

the beginnings".

(Windsor Local History Publications Group 1977).

Acknowledgements: Windsor Local History Publications Group; the late Mr. Reg Try.

See Also

|